Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting

Alberto Burri, an Italian artist recognized for having transformed the traditional easel painting into the Objet d'art (art object), was the subject of a large retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum entitled Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting which ended in January 2016. As a painter and sculptor, his experimentations laid the foundations for Process Art and the progressive Italian art form “Arte Povera”. The Sacchi (sacks) paintings, made from stitched and patched sections of torn burlap bags and often combined with pieces of abandoned clothing and paint bits, would cement Burri’s reputation worldwide during the second half of the Twentieth Century.

Born

in Citta di Castello, Italy on March 12, 1915, Burri was the son of a wine

merchant and an elementary school teacher. He earned his medical degree at the

University of Perugia. On October 12, 1940, Italy entered World War II and

Burri was sent to Libya as a medic in the Italian army. He would use his

surgical knowledge to treat the wounded soldiers mostly amputees and those

requiring skin grafts because of serious burns. May 8, 1943, his unit was

captured in Tunisia at the Battle of El Alamein and sent to a prison camp at

Gainesville, Texas for the remainder of the war.

|

| Alberto Burri, Sacchi |

He learned to paint there through a local YMCA with donated materials and his first paintings, inspired by an Umbrian nostalgia, were views of the desert from camp. Italian prisoners had an easier life in contrast to German, and Japanese prisoners. For one thing, officers were exempt from manual labor and they were allowed to mix with the local Italian American community and engage in recreational activities such as building religious altars, playing soccer, and tend vegetable gardens. Italian detainee artists assigned repaint local church. After the war, Burri’s POW experience had a transformative effect as the young Italian doctor resigned from medicine on his return to Italy and pursue art. He endured the remonstrations from family and friends with a tranquil determination upon his arrival to the age-old city of Città di Castello, in Umbria.

Italy

was wrecked after the war as its resources were nearly depleted. The Fascist

years created a limited intellectual openness that left the nation worn and harsh.

Eventually however a modern Renaissance spread as the country was gaining self-assurance

in its future with the artists in the forefront. Art was used to reexamine Italian

history and future prospects. Painters, poets, and intellectuals formed new

groups and cultural associations publishing journals, encouraging new ideas, and

promoting a new philosophy for the arts.

During the 1950’s a cultural exchange began between Italy and the USA. American artists such as de Kooning, Rauschenberg, Rothko, Twombly visited and lived in Rome. The city was a meeting place for critics, most notably James Johnson Sweeney who became the second director of Guggenheim Museum and a champion for Burri by acquiring three art works for the museum’s collection. Johnson and Burri would share a lifelong friendship that entailed Burri sending Sweeney every year at Christmas a signed miniature of a work exactly proportioned to fit in the palm of a hand. Through this good fortune, Alberto Burri along with Lucio Fontana emerged as the pioneers of post-war Italian art.

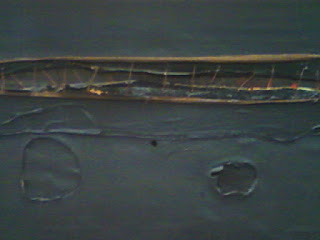

Dada

and Surrealism were early influences on Burri’s work. The paintings by Arp and

Miro that incorporated burlap as a ground prompted Burri’s own use of torn red

stained burlap. Burri expressed a new aesthetic integrating stitching, burning,

wood, metal, plastic, tar, cellotex (insulation material used in homes), and

burlap that transformed the paintings from a mere pictures into objects. His

repertoire of work included the Sacchi (sacks), Catrami (tars), Muffe (molds),

Gobbi (hunchbacks made by metal protrusions placed behind the canvas), Bianchi

(whites), Legni (woods), Ferri (irons), Combustioni Plastiche (plastic

combustions), Cretti, and Cellotex works. Burri would often mix and match the

different materials and systems. The

clean fissures of his Crettis were never accidental but guided by a scientific

approach: he was a knowledgeable chemist. Using torches he created burrows in soft

gooey tar or burned holes through clear plastic and laid over a stained patched

surface. Scholarly opinion viewed them as symbolic of the

gore and broken skin that he encountered during the war.

|

| Alberto Burri, Catrame 2, 1949 |